A brand is an intangible, emotional connection between vendor and customers — not a product, a company, a name, or a logo.

A brand is an intangible, emotional connection between vendor and customers — not a product, a company, a name, or a logo.

Successful companies, by definition, are adept at branding — regardless of industry, size, age, era, customer type, or geography.

This axiom, of course, includes real estate: residential, industrial, and commercial.

Branding a new real-estate development, controlled by one company, is fairly straightforward: Glean the needs, desires, and emotions of carefully targeted potential residential and business customers, convert those elements into a pithy slogan, message it back to said constituents, and fulfill the brand’s promise through effective execution.

Rebranding and redeveloping an old parcel of land, however — with a history of different uses and drastic changes, and now owned, controlled, and redeveloped by multiple companies — has a different set of challenges.

Chaotic Redevelopment

Welcome to the Strip District, a bastion of chaotic, noisy, endless redevelopment.

One looks around at the constant excavation and asks, Which developer is doing what, when, for what purpose, and for how long?

These are not trivial questions.

Without a single, clear roadmap/timetable of impending transformation and disruption, from all the developers, the result can be alienation of current and potential customers.

A few months ago, I moved from California, where I had lived for two decades, back to Pittsburgh, where I grew up and graduated from Pitt’s engineering school. I landed in the Strip District to bunk temporarily in the new home of a relative, until I can figure out where I want to settle.

The Strip District may sound like an area of ill repute, but that isn’t the case. The appellation is literal: it’s a half-square-mile parcel of land in Pittsburgh, on the south bank of the Allegheny River, roughly 20 blocks long by three blocks wide.

Brief History

Originally called Bayardstown and privately owned, the Strip became part of Pittsburgh in 1837. With proximity to river, rail, and roads, this sliver of land always has been a launching pad for change.

US Steel, Westinghouse, Heinz, ALCOA, and Armstrong Cork Company (whose HQ is now a seven-story apartment building), and many other industrial companies incubated in The Strip — and still do.

In 1906, it became Pittsburgh’s center of wholesale produce, after railroad tracks were removed from downtown proper. People bought and sold produce right from railroad cars.

To centralize and organize the produce commerce, in 1926, the Pennsylvania Railroad built the five-block-long (to accommodate the length of freight trains), 155K-sq-ft Pennsylvania Fruit Auction & Sales Building, which became known as the produce yards and the Terminal Building.

From around the country, trains would stop at the produce yards to offload cars of fruits and vegetables. This produce would be auctioned off to the middlemen, like my grandfather, on the massive concrete trading/storage floor. Those middlemen, in turn, would sell the pallets of produce to local grocery stores and restaurants. Finally, from the Terminal Building’s 75 100’x21′ loading docks, trucks would pick up the sold produce to deliver to the new buyers.

The wholesale-produce business in The Strip was a hotbed of activity that eventually replaced heavy industry and displaced many residences. But, its utility lasted only about five decades, as the airplane and refrigerated truck rendered the middleman obsolete to retailers. Accordingly, this method of commerce peaked in the 1950s and ended in the 1970s. Conrail bought the building from Penn Central (railroad), which had gone bankrupt.

Enter the Buncher Company, founded in 1949 by the late Jack Buncher. The son of Russian Jewish immigrants who grew up in the Strip District, Buncher was a scrap dealer and became one of the largest landowners in Pittsburgh (e.g., he sold the land that became Three Rivers Stadium). In 1983, he bought the Terminal building, and 55 acres of land, from Conrail and sold it the same year, for $1.1M, to Pittsburgh’s Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA).

The Strip’s Transition

The Buncher Company, which at one time owned over one-million square feet of Strip District land, played a key role in catalyzing its transition and rejuvenation.

The Strip always had a smattering of eateries, grocery merchants, warehouses, and machine shops, but never looked particularly good. For many years, Buncher had envisioned investing $400M to transform the Strip into offices, shops, apartments, and homes, but political battles impeded execution.

Fortunately, the dream endured.

In 2004, McCaffery Interests of Chicago became the new general partner in the Cork Factory Lofts (formerly the 1901-built HQ of the Armstrong Cork Company). Charles Hammel III and Robert Beynon had purchased the buildings in a 1996 bankruptcy. The Lofts opened in 2006, followed by the marina and retail complex in 2008.

In 2007, Buncher built the Strip’s first hotel: a 143-room, eight-story Hampton Inn & Suites — a stone’s throw from the David L. Lawrence Convention Center (opened in 2003), across the river from PNC Park (Pirates) and Heinz Field (Steelers), both of which opened in 2001.

In 2010, Buncher reacquired the Produce Terminal, in a three-way real-estate swap with the URA, and ultimately sold it back (again) to the URA in 2014, for $675K.

After that, the Terminal was home to a revolving door of merchants, who set up stands and storefronts to sell their wares to the public, as seen in the Tribune-Review photo below from December 2012.

In April 2016, Oxford Development opened a 300-unit apartment building called The Yards at 3 Crossings, managed by Chicago-based McCaffery Interests, followed by the Stacks at 3 Crossings in 2018.

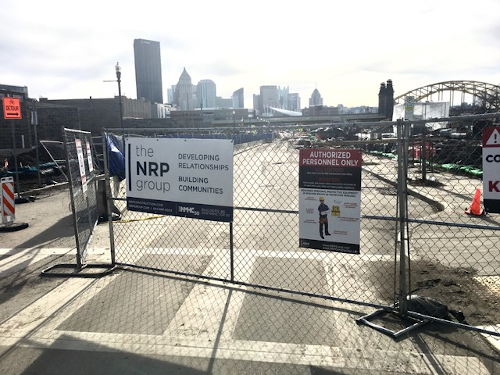

Cleveland-based NRP Group LLC, in 2018, opened phase one of the 443-unit, upscale Edge Apartments, on the Riverfront Landing development owned by Buncher Co. NRP began building phase two in January 2020 — causing a 29-month shutdown of a five-block section of Waterfront Place (see photo below).

Also in 2018, Buncher sold to Laurel Communities four parcels of land, at $405K, adjacent to the Terminal building, for 46 brownstone-style townhouses. Each is selling for almost $1M.

Talk about turning crap into gold!

In the spring of 2019, after five years of negotiation, McCaffery secured from the URA a 99-year lease, for $2.5M, on the Produce Terminal. McCaffery is expected to invest upwards of $50M to revamp it as an upscale panoply of shops, cafes, and offices. The new Terminal is scheduled to open in August 2020.

McCaffery also bought the former warehouse across the street from the Terminal, at 1600 Smallman Street, to convert it — for another $50M — into, you guessed it, offices and shops. The city will spend $23M to revamp Smallman Street, which currently is pockmarked with axle-damaging potholes.

Pros & Cons

The Strip is now home to a slew of tech-based companies — Apple, Argo AI, Aspinity, Aurora Innovation, Blue Belt Technologies, Bosa Nova Robotics, Branding Brand, Facebook, Honeywell, Robert Bosch GmbH, Uber’s Advanced Technology Group (self-driving cars), Voci Technologies — as well as Oxford Development, Rycon Construction, and the Burns White law firm.

The list of developers jumping into the Strip District Gold Rush is growing and causing massive disruption. At every turn, there’s a new project under construction. Constant noise and dirt, and road closings without warning. Shoppers descend every weekend, making Penn Avenue look like the Santa Cruz boardwalk — with a paucity of parking spaces to accommodate all the cars.

Alas, there’s no concerted effort from developers to communicate the roadmap/timetable of transformation — making living, working, and shopping here unsettling.

Don’t get me wrong: Stimulating business growth is imperative in Pittsburgh, which is in dire need of it.

I heard Gus Faucher, PNC’s chief economist, tell two business audiences in as many days, in January 2020, that Pittsburgh and Pennsylvania lag the rest of America in GDP growth. His October 2019 edition of “The PNC Economic Outlook,” focusing on small and mid-size business owners in Pennsylvania, stated this: “Pennsylvania has one of the slowest-growing populations in the country.”

Growth is good. Growth is positive. Growth is mandatory. But, if the growth reduces the quality of life, it will repel and alienate residents and businesses. People can tolerate a certain degree of reasonable inconvenience, in a reasonable timeframe, if they know what’s coming down the pike.

Unreasonable inconvenience? Protracted timeframe? Not so much. And, nobody likes constant surprises.

On January 23, 2020, in a conference room at the Burns White law firm, I attended a town meeting of 100 concerned Strip District residents and business owners, who were there to hear real-estate developers give updates about the future of the “neighborhood.”

After listening to the presentations, I asked two questions:

|

Apparently, my questions, which nobody answered, resonated. Shelby Cassesse of KDKA TV interviewed me afterwards to get my opinions on the air. I’m certain I was expressing the concerns of many.

At the meeting, we learned that 21st Street would be closed for two weeks while the Terminal Building connects to city water and sewage. Guess what: It’s going to be at least four weeks. Surprise!

Prior to the town meeting, in late December 2019, we learned on local TV news that five blocks of Waterfront Place would be closed for 29 months, so NRP can build phase two of the Edge Apartments. That’s 2.5 years. Surprise!

Parting Advice to CEOs

If you build it, will they come? So far, that’s been the case. But, as new waves of people move into the Strip District and experience the uncoordinated chaos, that will change.

More people, same roads — frequently closed without warning — means more congestion and frustration.

Bottom line: chaos and poor communication ruin relationships — personal and business — and, therefore, brands.

As stated in the first paragraph, a brand is an intangible, emotional connection between vendor and customers. In the Strip District, there is no single vendor (there are multiple vendors), so there is no brand — other than chic for intrepid outsiders, who hear that the Strip is “lit,” and chaos for insiders, who hear jackhammers and backhoes’ back-up beepers all day long.

I have it on good authority that the disruptive construction in the Strip District will last for 15 years. 15 years! I am, perhaps, the only resident who knows this. The developers are not handling this situation properly. They can, but they’re not.

Remember: ROI and alienation don’t mix.

It’s laudable that the developers are creating something special from a scrap heap. But, if they build too much, too fast, too disruptively, too chaotically, too noisily, and too secretly, the current lure of the Strip District will fade.

I recommend that, despite being competitors, all the developers work together by forming or hiring a single entity, and creating a single website, to convey a constantly updated roadmap/timetable to the residents and businesses of the Strip District.

Branding by committee doesn’t work. Giving separate interviews to the press won’t cut it.

Rebranding the Strip District can succeed only if one, unified supply-side entity manages it, and if the demand-side constituents are enjoying and benefiting from the changes — and recruiting others to locate here.

POSTSCRIPT #1: JMC Holdings to Build 21-Story Office Tower at 1501 Penn Ave (02.20.20)

© 2020 Marc H. Rudov. All Rights Reserved.

About the Author

Marc Rudov is a branding advisor to CEOs,

producer of MarcRudovTV, and author of four books